The Evolved History of CNC Machining

Computer Numerical Control machines revolutionized the manufacturing industry—but how did they get their start?

—

If you were to take a tour through the shop of every manufacturer in your area, you’d notice that every single one uses some type of CNC machine in their operation. In fact, you could go to any manufacturer in just about any part of the world and find them there. Computer numerical control machines (also known as CNCs) absolutely revolutionized the reality of the manufacturing industry, so much so that modern day machine manufacturing would be rendered impossible without them.

So when did CNCs first get introduced?

Their origins can be traced back to the 1940s and a man named John Parsons. Parsons was an engineer who initially started working for Sikorsky Aircraft building helicopter rotor blades, but when they started to fall, he knew he had to find a better solution to building them. After realizing that making metal stringers for the rotors would be more efficient than making them out of wood, he invited another engineer named Frank Stulen to help him bring his idea to life. Stulen’s brother even joined in on the action, and they ended up developing a 200-point program that was inspired by the IBM punch card system. It was a laborious process, and the beginning of what’s known today as 2.5 axis machining.

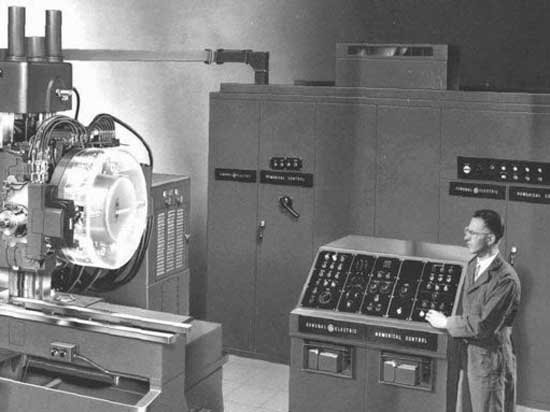

A couple years down the road, the US Air Force caught wind of Parsons’ invention and employed him to build his machines for them. They later included a team of engineers from MIT, who ultimately ended up buying the company out from under Parsons. The MIT team developed a machine that had an accuracy unlike any other seen before. This design was different as it used a 7-track punch tape and generated clock cycles connected to a converter that would automatically move the machine’s controls (whereas Parsons’ machine required three people to operate it). That same year, in 1952, the first commercial CNC lathe was demonstrated to the public which catapulted their popularity. Boeing itself, one of the top-dog aerospace companies, remarked upon how efficient the machines proved to be, saying, “Numerical control has proved it can reduce costs, reduce lead times, improve quality, reduce tooling, and increase productivity.”

Even with its raving reviews, sales were slow at the start. In the late 50s, it was extremely expensive to run computers, which made CNCs relatively inaccessible to many companies. But once minicomputers were introduced in the 60s, prices fell, and sales rose as microprocessors made operating the machines even easier. Eventually, the operation of the machines went from factory floors to controlled office spaces as technology advanced even further. John Runyon, an engineer on MIT’s team, developed a method of coding with subroutines which would reduce production time from 8 hours to 15 minutes. With the future of CNC machines kicking into high gear, the Air Force started pushing for the development for a generalized coding language for them. This is when Doug Ross and Harry Pople entered the frame.

Doug Ross and Harry Pople are the two engineers responsible for the creation of Automatic Programmed Tool, or APT. This text-reliant program makes it possible for computers to process instructions for cutting complex parts into understandable commands and actions. Sponsored by the Air Force, its creation changed CNC entirely and lead to the creation of computer aided manufacturing systems (also known as CAM), which are still in use today.

Image from one of Richards’ F1 wins.

This is not even close to the entirety of CNC machine history, but these key moments laid the foundation upon which today’s CNC machines sit upon. They are now an integral part of the modern-day machine manufacturing process. Without CNCs, the founder of James Engineering, James Richards, would have never invented his all-encompassing surface finishing machines, as they are meant to be paired with CNCs. But before his machines came to be, he worked on transmissions for F1 racing cars. He got his start in a mechanics shop as a teenager and quickly realized that not only did he love mechanical engineering, but he had a natural knack for it. So when he started his career in F1, it came as no surprise to anybody when he lead racers such as Nelson Piquet and Gordon Johncock to their individual wins. He began working on his deburring machines (which he would later call the MAX Series) in the 1980s and has continued to shape the reality of manufacturing ever since. He never lost his love for cars and has worked with countless automotive companies, as well as big-name aerospace companies like Boeing, Pratt & Whitney, and Bell Helicopter.

Engineering is ever evolving and is constantly changing the manufacturing world as a result. Bright engineers such as John Parsons, Doug Ross, and James Richards have made their marks for the better, making once laborious processes efficient and precise. Because of them, consumers, pilots, racecar drivers, train conductors, chefs, and other dreamers alike are able to pursue their passions with confidence.

Every day we continue to write machining history—so what will our future history books have to say about CNC machining and manufacturing as a whole?